Liming Cai

Credit: Sarah Wilson

Stengl-Wyer Postdoctoral Scholar, Department of Integrative Biology. Interviewed by Nicole Elmer.

Where were you before UT and what did you study?

I did my doctoral research on plant evolutionary biology at Harvard. My research is always themed around plants and phylogeny. I studied the systematics of the cabbage family Brassicaceae for my undergrad thesis. And my doctoral research gave me the opportunity to work with the most glorious group of plants in the world – Malpighiales – which has more than 16,000 species, with tropical plants like passion fruits, rubber trees, mangroves, willows, as well as the world’s largest flower! These astonishing diversities evolved almost overnight during the Mid-Cretaceous period.

What got you interested in studying the phylogenetics (evolutionary development and diversification) of plants?

Like many others in the department, I loved digging up soil when I was a kid. In an introductory biology course I took as a freshman, I completed an inventory report of all 152 plant species I could find in our half-acre garden. I grew from knowing almost nothing about plant taxonomy to becoming kind of a go-to person. Later on a field trip in my sophomore year, I was totally thrilled to see the cute dwarf alpine Brassicaceae. After the trip, I was pretty determined to become a botanist.

Where do you see your research agenda heading at UT?

My work here will hopefully shed new light into plant parasitism. Parasitic plants feed off other plants and may not be photosynthetic.

“Texas has a quite rich diversity of parasitic plants”

How do the Biodiversity Collections, like the Billie L. Turner Plant Resources Center at UT, figure into your work?

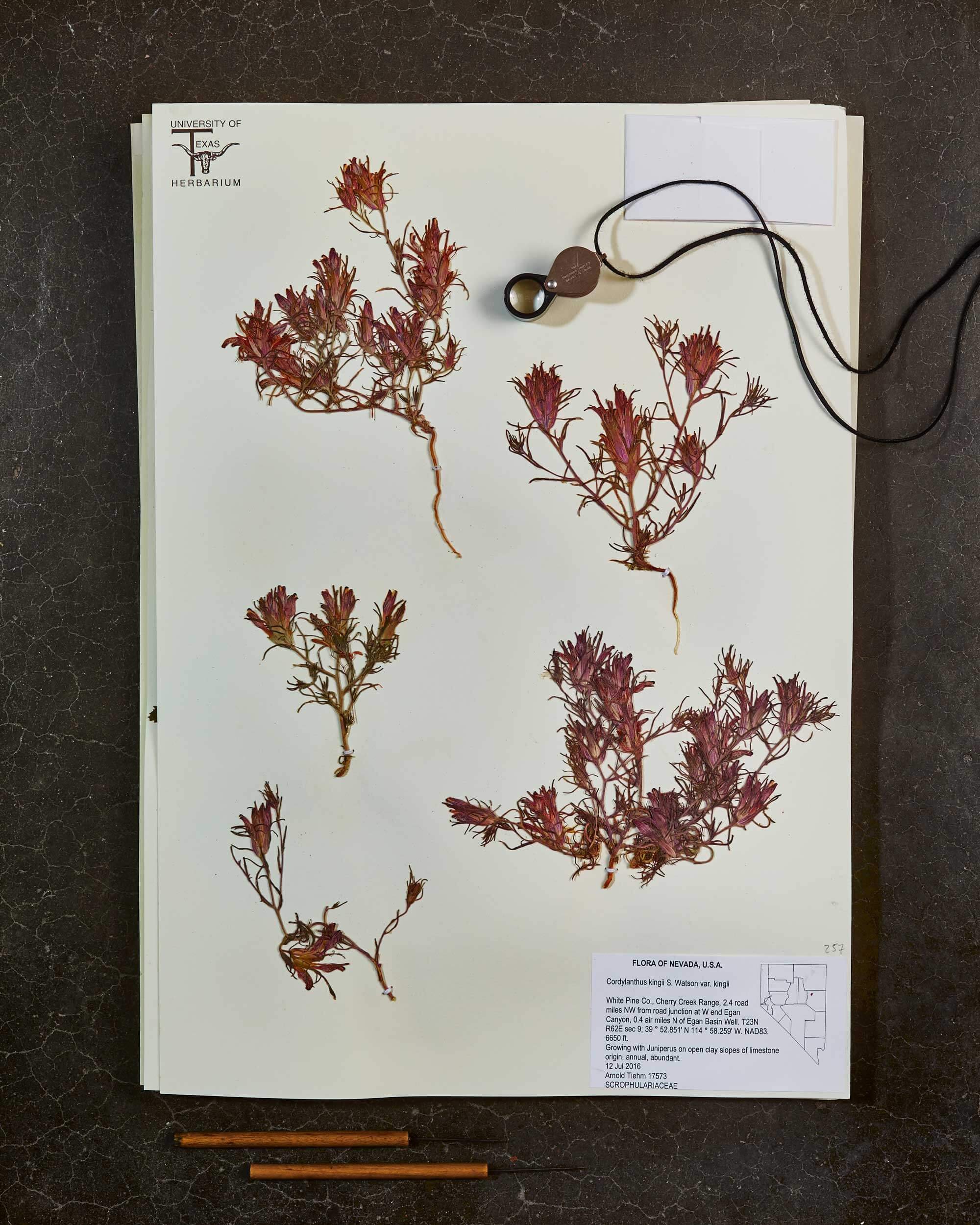

Even before I became a scientist, I was a huge fan of museums and natural history collections. They play such an important role in advancing education and science in every corner of the world. The specimens held at the Turner Plant Resources Center provide vital material for my research at UT, exploring the parasitic broomrape plants (Orobanchaceae). There are more than 60 Orobanchaceae species in Texas, the majority of which can be found in our herbarium.

Does Texas present a unique situation, challenge or benefit for your research?

Texas has a quite rich diversity of parasitic plants. The false foxglove and paintbrush are common wildflowers we can enjoy from spring to early fall. They are hemiparasites, meaning that while they take nutrients from their hosts, they are also photosynthetic and generate their own energy. On the other hand, if we travel to the mountainous regions in and around Big Bend National Park or the deserts in the west, we can find holoparasites such as the broomrapes and American cancer-root. These plants are completely non-photosynthetic and they only emerge above ground when they are flowering.